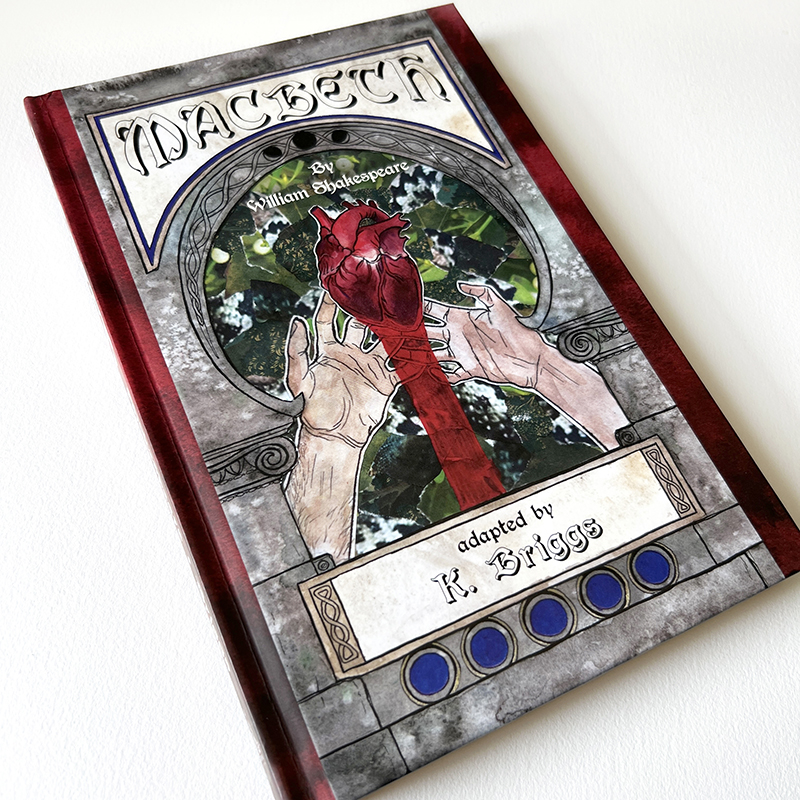

K. Briggs’s stunning adaptation of Macbeth comes out on the 25th of July! You can pre-order a copy here.

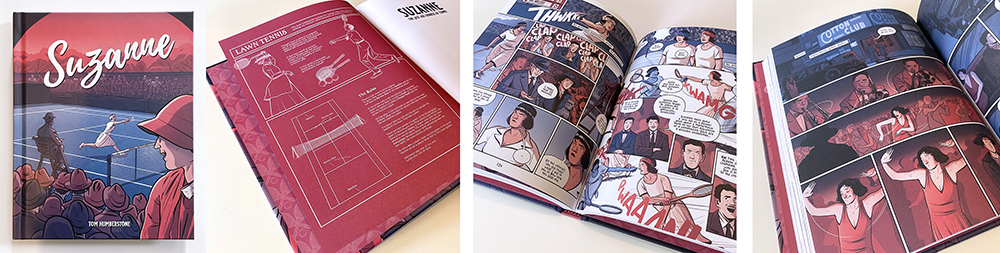

Below they’re interviewed about the book by Tom Humberstone, creator of the wonderful Suzanne – The Jazz Age Goddess of Tennis.

Tom: Macbeth is one of the most popular of Shakespeare’s plays for stage and screen adaptations. As with any Shakespeare adaptation, I would imagine there’s something both thrilling and daunting about being in conversation with centuries of other people’s interpretations. Were there any choices that other adaptations make that you were keen to avoid, or things that inspired or influenced your own approach? Have you felt frustrated that other adaptations misunderstood or missed a certain aspect that you felt was crucial to the play? Do you have a favourite? (except for yours of course!)

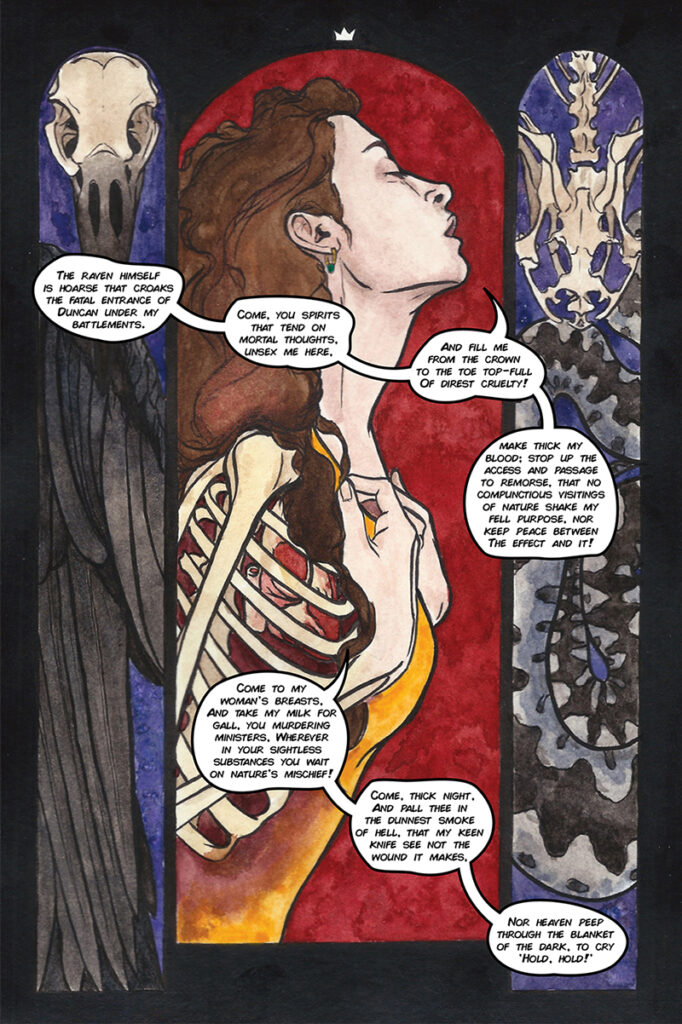

Briggs: It is absolutely one of the most popular Shakespeare plays for adaptation! As I was working on mine not one, but two Macbeth films came out; both of which I avoided so as not to influence my interpretation mid-process. From the outset I wanted to pay close attention to the women of the play – what are their motivations? What are their relationships to power in this world? And then, what about the peasant population of Scotland? Where do they fit into these wars and upheavals? I’ve felt frustrated by their absence in other interpretations, and also the motivations of the Weird Sisters, Lady Macbeth, and Lady MacDuff being just “women are crazy”. I have a favorite! Throne of Blood, directed by Akira Kurosawa; Toshiro Mifune is sublime.

Tom: Am I right in saying that you drew a lot of this during lockdown? Did that impact the way you approached the adaptation or impact the way you felt about the play in any way?

Briggs: Ooft, lockdown kind of blurs together, if I’m honest. But this book was pure escapism for me; I got to dive headfirst into my medieval art obsession and transport myself back to Scotland, which I miss terribly.

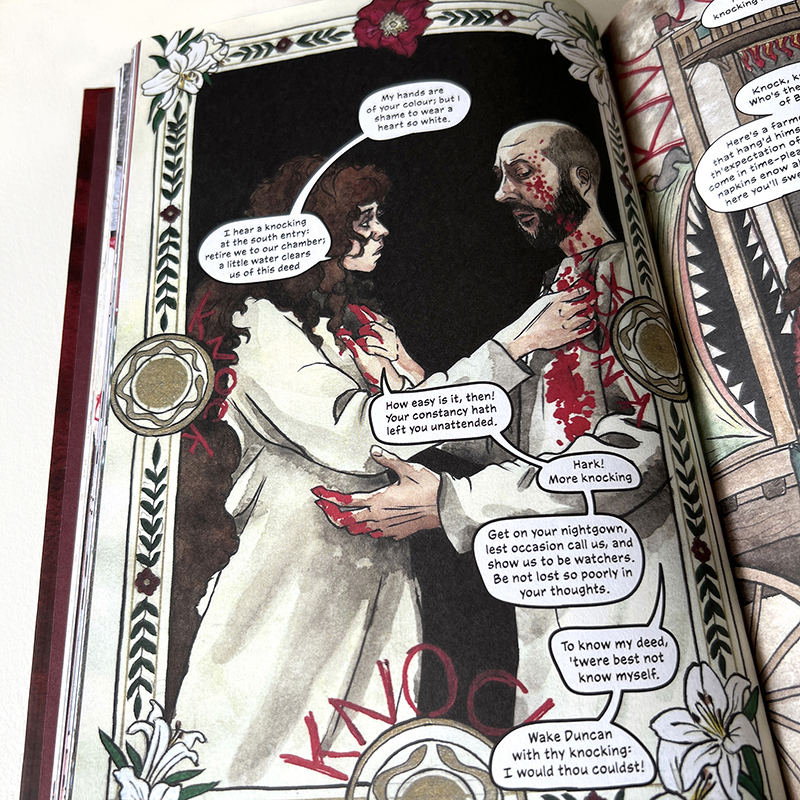

Tom: On the page, there’s a lot of playful symbolism, experimental panel structures, and of course your gorgeous use of collage. I’m curious – was that all there in script-form before putting pencil to paper? Or did you discover things on the page? Or was it a mix of the two? I suppose I’m curious about your process here. How did you go from manuscript to finished comic?

Briggs: The first step was to put page breaks in the script; how much information and dialogue could I logistically fit on a single page? I think Alan Moore once said no more than 250 words per page, so I started there, then considered what would make a complete thought on a single page. That takes time, and as I worked I changed a few things here and there, added an extra page to give space, etc. When it comes to the art, I think my process comes from my painter background – I don’t do a roughs pass, I just work up a page from start to finish, discovering it as I go. And I work out of order; since I have the script figured out already, I work on whatever page strikes my fancy on a given day. If I forced myself to work in order I’d get bored or rebellious; if I felt like drawing witches, I’d draw witches, simple as that. And then as far as the content of the pages, there’s what’s been said/done and there’s what it means. I try to incorporate something of what it means in every page. What going on between the words?

Tom: The comics medium is an entirely different beast to the stage. Why did you decide that Macbeth needed to be told as a comic? And what do you think the medium was able to bring to the play that other mediums would struggle with? What were the challenges?

Briggs: It’s a partially selfish answer – because I thought it was cool. Also, this book began life as a entry to the inaugural Graphic Shakespeare Competition back in 2016. There was a call for entries, so I sent in Act 1, Scene 1. There’s already an academic interest in Shakepeare as sequential art, and I can understand why. It’s the perfect balance – a reader of the play can’t get the extra information an actor’s interpretation would provide, a watcher of the play can’t go back and re-read a passage they didn’t quite catch, a watcher of a film adaptation is locked into the film’s pacing (unless they’re quick with the pause button). A comic has both visual and textual information and the reader is empowered to approach Shakespeare at their own pace. But a challenge that came up right away was sound effects; bells, thunder, lightning, and wailing all play important plot roles in Macbeth.

Tom: Do you have plans/hopes to adapt other Shakespeare plays as comics? Is there something about Macbeth that you felt worked especially well in comic form that wouldn’t work as well with other plays?

Briggs: I have an idea I’m putting together about The Tempest. Another one of my favorites, it has multiple stories going on simultaneously that the play switches back and forth showing. It’d be great to do it with a few other artists, each of us getting to interpret a subplot of our own. The Tempest and Macbeth are some of the shorter Shakespeare plays, so that counts for something – 180 pages is the longest comics I’ve ever done!

Tom: There’s an incredibly tactile quality to your art. With paint, tape, newsprint, pencils, gold leaf pens and countless other beautiful, tangible details. In my experience it can be hard capturing the quality of these things when scanning or photographing finished art. Was that tricky at all? Or is this something you are used to at this point?

Briggs: Thank you, I appreciate that. I really enjoy creating those layered textures. It’d get tricky only when my collage got too deep for the scanner to pick up, then it’s a matter of setting up the most even lighting possible and taking a bunch of photographs to try to capture the effect. But as far as weird collage stuff, I’m used to it. And my long-suffering scanner can attest to the many hours its been subjected to me pressing down a collage as hard as I can onto its glass.

Tom: Another thing I noticed about your panel layouts: No two were exactly the same throughout the book. Was that always the plan going in? Did you associate certain layouts/colours/panel shapes with certain characters? For instance, I noticed the witches were portrayed using just black, white and red and the pages were divided into segments of three.

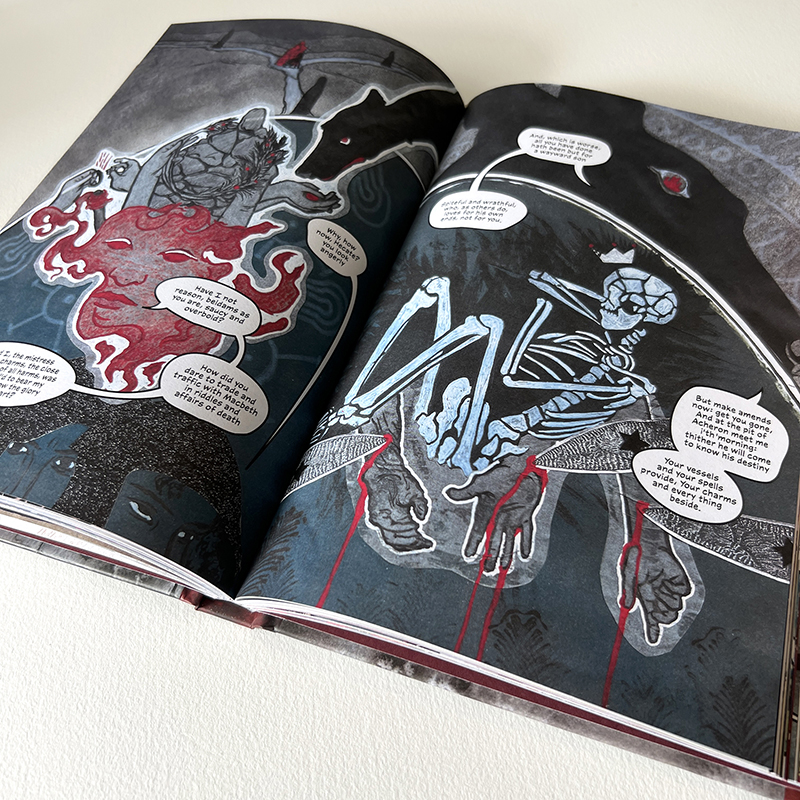

Briggs: Yes, the Weird Sisters are always in grey tones with pitch-black robes and blood-red accents. I wanted them to be out of time and space with the rest of the book – they’re beyond time and the material plane, operating on their own dimension they sometimes allow Macbeth to access. In the very first scene they’re calling down the blood-red that will serve as a symbol for evil and nefarious deeds throughout the whole book. And yes, it was always the plan to not have a plan, to let every page and panel layout be in service to the text. However I felt I could be interpret what was going on internally and externally, that’d be the panel layout.

Tom: A lot of the pages, by design, called to mind the Bayeux tapestry and stained glass windows. Are those art styles that have always fascinated you or was it more a case that they were especially suited for this story?

Briggs: Yes! And medieval illuminate manuscripts. Western comics traditions are rooted in all of these, because they’re examples of sequential art, too. Comics, thanks to paper and the printing press, are just more accessible versions of these art making traditions. I’ve been obsessed with medieval European art for a long time, it’s so fraught and a brilliant combination of stylization and realism. What are the rules of medieval art? What’s a lion look like? Who knows! I love it. And then on top of that, the real historical Macbeth ascended to the throne of Scotland in 1040, so I wanted to also draw from what would have been his contemporary art cultures, such as the Book of Kells.

Tom: A well-known aspect of making comics is that the artist is doubling as actor, make-up artist, costumer, set-designer, director, cinematographer, colourist, editor, stunt co-ordinator etc. – while that’s the case for all comics, it feels especially relevant here. As you sat down to work on a page, did the sense that you were putting on a full theatrical production on your own feel intimidating? Exciting? A combination of the two?

Briggs: So exciting. As a teen I was a theater nerd, especially living for the Shakespeare performances we’d do once or twice a year. This comics became my own production of Macbeth, and of course I cast myself as the best part – Lady Macbeth. The most intimidating part was the fight scenes, I didn’t feel very confident in drawing bodies in action. So, practice! I drew pages and pages of gesture drawings to build up my skills.

Tom: At 180 pages, this was a huge undertaking. How did you keep yourself motivated, disciplined and on schedule? Did you have a strict routine? Any tips for how you tackled the mental and physical ups and downs of a long-form project like this?

Briggs: Hoo boy, it was an undertaking indeed. But I tried to keep a “how do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time” mentality. Figure out how many pages per week I should ideally complete, and then celebrate every time I finished one. There’s a big dose of Know Thyself in there as well – I genuinely get a dopamine hit when I check something of a list, so I had multiple lists going. On my wall, in my sketchbook; every page done checked off somewhere where I could see my progress accumulating. I also kept production to standard business hours and didn’t make art on weekends; my partner works a 9-5 so it was important to me to make time to hang out together and have hobbies and downtime. Breaks and time off aren’t a luxury you “earn”, they’re a necessity to human life and the creative process. But it was intense. After I finished I took a whole month off to do nothing, and it took another three months after that before I wanted to drawing anything.

Order your copy of Macbeth here!

Tom Humberstone’s Suzanne came out in 2022. It tells the incredible story of Suzanne Lenglen, a woman who changed the face of sport and society in the trailblazing jazz age. This beautiful graphic novel explores how a figure both enormously influential and too-often overlooked battled her father’s ambition, bias in sporting journalism, and her own divisive personality, to forge a new path – and to change sport forever.